Kurt Cobain, 25 Years Later

Kurt Cobain died twenty-five years ago today. When I heard the news, I was sitting at my desk at Details magazine, where I was working as a music editor. (The office was on the corner of Broadway and Canal Street; I had a great panoramic view of Brooklyn, lower Manhattan, and New Jersey, when I remembered to turn my chair away from my desk and look out the window.) I had spent time with Nirvana in both Germany and Seattle over the previous two years for a pair of feature articles, a span of time that felt endless then and seems like an eyeblink now.

Kurt Cobain died twenty-five years ago today. When I heard the news, I was sitting at my desk at Details magazine, where I was working as a music editor. (The office was on the corner of Broadway and Canal Street; I had a great panoramic view of Brooklyn, lower Manhattan, and New Jersey, when I remembered to turn my chair away from my desk and look out the window.) I had spent time with Nirvana in both Germany and Seattle over the previous two years for a pair of feature articles, a span of time that felt endless then and seems like an eyeblink now.

Another editor came into my office and said she had heard that Kurt Cobain was dead. At first I assumed this was just a jumbled rumor—only a few weeks earlier, he had been hospitalized in Rome for what was billed as an overdose (only later explained as a suicide attempt). I had been told what he said as he came out of his coma–“Get these fucking tubes out of my nose”—which had been spun as a manifesto of his indomitable will to live, or something like that.

Assuming that I would get an official explanation of how it was all a big misunderstanding, I called one publicist at Geffen Records who worked with Nirvana and got his voicemail, and then another one, with the same result. Then I called a third one, who hurriedly rushed me off the phone and forwarded me to the first one, who said wearily that Geffen didn’t have a statement to make yet. By the time I was done making my phone calls, cable news had photos of Cobain’s dead body.

Only moments for shock and grief to settle in: we had to figure out how we were going to cover the story. After a quick editorial huddle with my boss, David Keeps, I rushed out of the office to get my Nirvana notebooks, which had various useful addresses and phone numbers. I took the subway home to Brooklyn and spent an hour going through all my files, with MTV on in the background, where Kurt Loder covered the breaking story, interspersed with Nirvana music videos. For the life of me, I could not find the notebooks.

Defeated, I came back to Manhattan, and found that I had stashed the notebooks in a desk drawer in my office (reasoning that they were unusually important and I would want easy access to them at some point). Of course. The magazine put contributing editor Mim Udovitch, who had recently interviewed Courtney Love for the release of Live Through This, on the last plane to Seattle that day—where she found herself boarding with a small cohort of other New York writers on the same grim mission. Mim went under protest, saying that if she stayed home, Courtney would call her. We all scoffed at this, thinking that it was hubris, but Mim turned out to be right: she got nowhere in Seattle, but there was a message on her answering machine when she came home. (1994: not a time when most people had cell phones.)

We also paid for Dean Kuipers to report what he could from the Seattle rock scene that weekend; we never printed the results, but I read his dispatch. I remember it as a ten-page fax, eloquently written, laying out everything he did in Seattle, and how everyone he spoke to was gobsmacked with grief and politely made it clear they had zero interest in cooperating with the media.

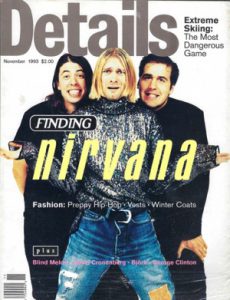

That night, I kept listening to Nirvana’s music, and it tore me inside-out. I ended up writing a remembrance of Cobain for the magazine, trying to make sense of his life and death. You can read it here. If you’d like to read the 1993 cover story I wrote on Nirvana (at the time of In Utero), I archived it here. If you’d like to read the roundup I did this week for the New York Times on Cobain-oriented things to watch or read (books, articles, videos, poems, comics), it’s on their website here.

Can I say that I feel like Cobain’s death marks the end of my youth without it sounding melodramatic and “the day the music died”? Because it wasn’t that I woke up the next day a changed person, having shed my innocence. But I was just a year and a half younger than Cobain and, aside from that one kid in my high school I wasn’t close to, I don’t think I had known anyone my age who had died before him. Certainly not anyone I had spent hours talking to about life and art, as I had with him.

Nirvana was one of the first bands I ever wrote about: the first time I hung out for hours backstage, the first time I rode on somebody’s tour bus. I made mistakes in how I covered Kurt—there’s things he said that I had accepted too credulously, there’s a secret somebody else told me that I shouldn’t have shared. We had been friendly, if not close, but by the time he died, I’m pretty sure he had crossed me off the list of journalists he liked. (I didn’t know it at the time, but I figured it out later.) Kurt’s death was a lot more than my life lesson, but it nevertheless made me step back and think hard about a lot of things, and to change some of them.

I look back now and I can see how I hurtled through my early 20s, full of enthusiasm and good intentions, and how that often worked out for me, both in my writing and in my personal life, and how I learned that wasn’t always enough. Vulnerable and confused and loud, Nirvana is still the soundtrack for that time in my life.

posted 5 April 2019 in Archives, Articles and tagged New York Times, Nirvana. no comments yet